Based on the 5 Big Ideas in Beginning Reading

U.S. National Reading Panel (2000)

StepsWeb is a research-based online literacy program for learners of all ages from 5 years of age to adult. It covers key aspects of literacy and language development and covers the processing skills involved in literacy as well as the ‘knowledge’ aspects.

StepsWeb provides a structured, cumulative approach to literacy, which encompasses and develops the six key elements often referred to as the Big 6 of Literacy (Konza, 2014)

The concept of the Big 6 of Literacy builds directly on the work of the U.S. National Reading Panel (2000), which identifies five essential components of reading instruction:

In later years, researchers such as Dr. Deslea Konza (2014, Edith Cowan University, Australia) emphasised the importance of oral language as the foundation supporting all five of these components. This extension led to the adoption of the Big 6 framework, which recognises oral language as the critical underpinning of effective literacy development while retaining the five key elements identified by the National Reading Panel.

Oral language refers to a learner’s ability to understand and use spoken language, including listening, speaking, vocabulary, syntax, and narrative skills. It's the foundation that supports all other reading components. Without it, learners struggle to understand phonemic patterns, build vocabulary, or make meaning from text.

To make the most of the oral language component on StepsWeb, we highly recommend learners use headphones as they work through the online program.

While oral language is not directly assessed, StepsWeb supports its development through clear, and consistent speech modelling across the online Course:

Most activities on StepsWeb involve listening for sounds and matching those to a variety of stimuli. Some have a particular emphasis on comprehension and concepts:

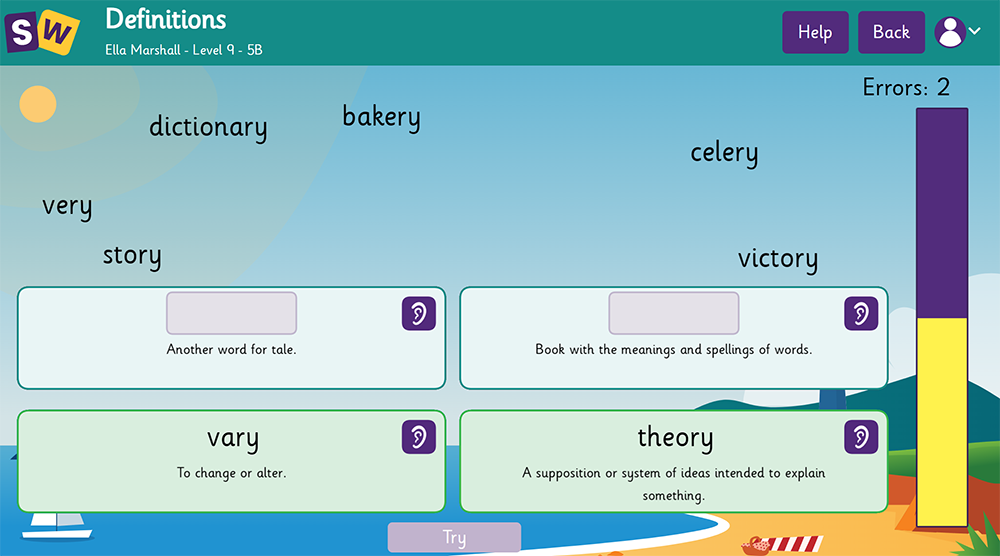

Definitions – matching a word with its more formal, dictionary-style definition.

Clues – onset + rime awareness

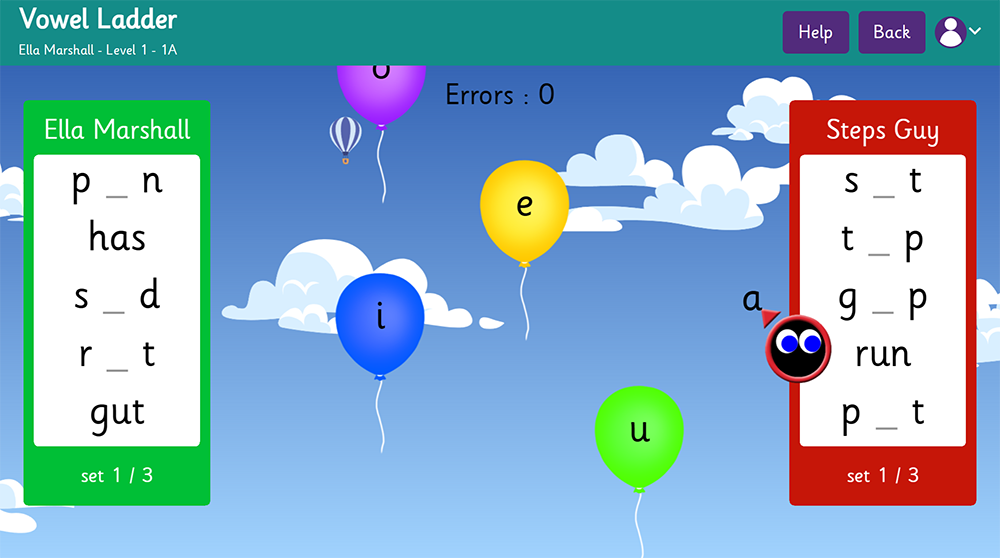

Vowel Ladder (game) – phonemic awareness, auditory discrimination, phonic knowledge, blending, decoding/encoding skills

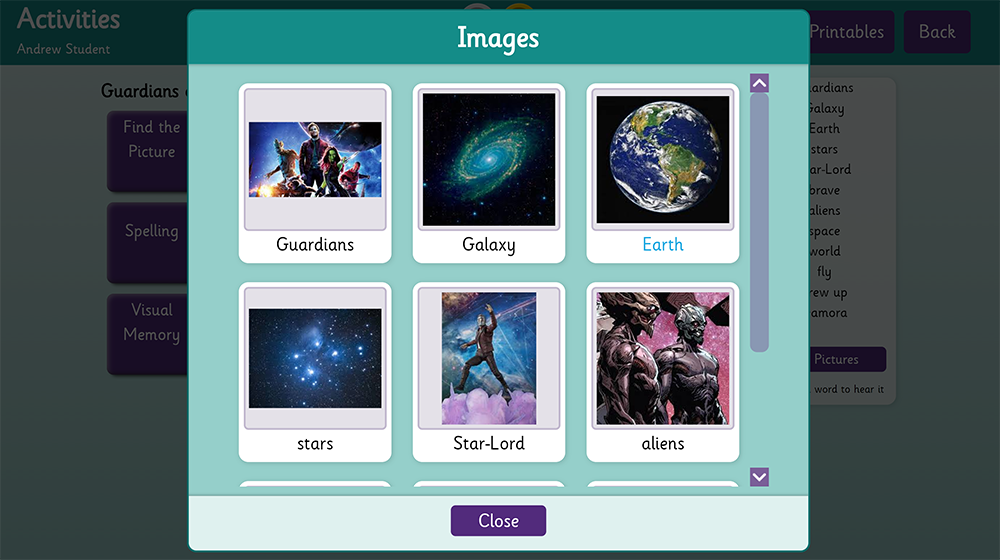

Find the Picture

The main emphasis on oral language comes in the workbooks and hands-on resources, which involve more explicit and interactive teaching. These have a strong emphasis on oral language development, including receptive and expressive vocabulary and comprehension

Byrnes, J. P., & Wasik, B. A. (2019). Language and literacy development: What educators need to know. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Education Review Office. (2024). Good practice: Oral language development in the early years. Wellington, NZ: Education Review Office.

Hulme, C., Snowling, M. J., et al. (2022). Scaling up early language intervention in educational settings: First steps matter. Oxford Review of Education.

Konza, D. (2014). Teaching reading: Why the “Fab Five” should be the “Big Six”. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 39(12).

Lindfors, J. W. (1987). Learning how to mean: Explorations in the development of language. London: Edward Arnold.

Scharer, P. L. (2018). Children’s language and learning (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Vukelich, C., Enz, B. J., Roskos, K. A., & Christie, J. (2020). Helping young children learn language and literacy: Birth through kindergarten. Hoboken, NJ: Pearson.

Wiesner, D. (1991). Tuesday. New York, NY: Clarion Books.

There is considerable research from all over the world into the importance of different aspects of phonological awareness. Phonological awareness is often a major weakness in learners with dyslexia or similar processing difficulties.

Phonological awareness is often referred to as phonemic awareness, but there is a crucial difference between these terms.

The term ‘phonemic awareness’ comes from the word ‘phoneme’, which is a single sound in language. This includes the following individual skills:

The term ‘phonological awareness’ comes from the word ‘phonology’, which is the sounds and sound patterns of language. Phonological awareness is therefore a broader term than phonemic awareness and encompasses the following:

Phonological awareness is purely processing the sounds and sound patterns in language, not understanding how those sounds map onto text, which is referred to as phonic or orthographic knowledge.

However, it is an essential precursor to phonic knowledge. There is no point trying to learn what letters represent what sounds if you are unable to process those sounds in language in the first place.

The following activities are specifically designed to develop phonological awareness. Some of these activities only involve processing the sounds or sound patterns themselves (phonological awareness) and some make the link with the written word (phonological awareness + phonic knowledge).

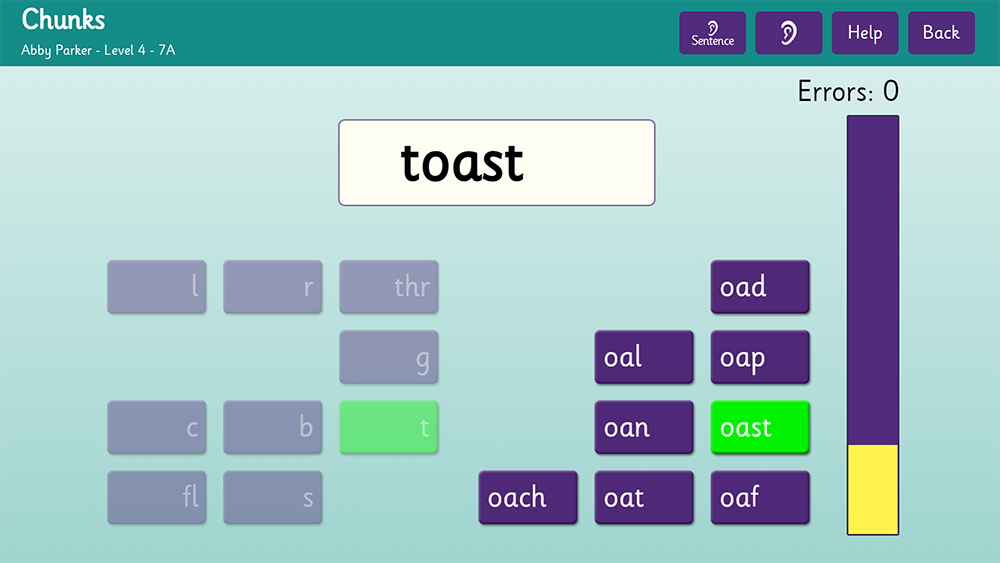

Chunks – onset + rime awareness

Initial Sounds – onset + rime awareness, phoneme transposition

Vowel Sounds (game) – phonemic awareness, auditory discrimination and phonic knowledge

Vowel Ladder (game) – phonemic awareness, auditory discrimination, phonic knowledge, blending, decoding/encoding skills

Jigsaw (games) – phonological awareness, phonic knowledge, categorization

Alphabet (Supplementary Activities) – phonic knowledge, phonemic awareness

Spelling – auditory discrimination, phonemic awareness, decoding/encoding skills

Syllables – auditory syllabification

Short Vowels (Supplementary Activities/Phonological) – auditory discrimination and decoding/encoding

Initial Sounds (Supplementary Activities/Phonological) – Phonemic awareness, auditory discrimination, phonic knowledge

Sound Splits - using phoneme-grapheme skills to split words into individual phonemes

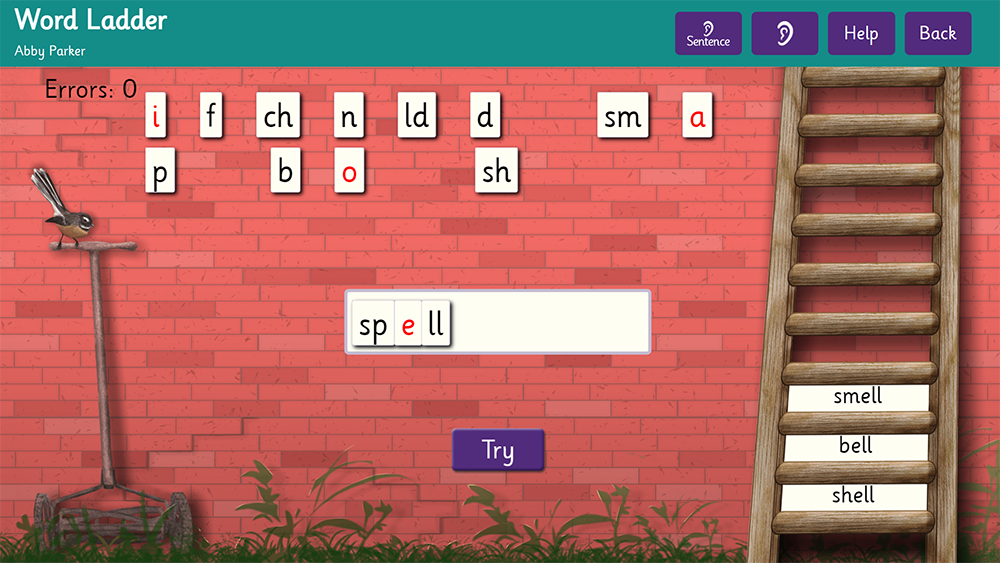

Word Ladder – phoneme transposition

Sound Chunks – blending onset and rime

Find the Letters – phoneme/grapheme matching

Feed the Kiwi – matching phonemes/graphemes within a word

“The majority of preschoolers can segment words into syllables. Very few can readily segment them into phonemes. The more sophisticated stage of phoneme segmentation is not reached until the child has received formal instruction in letter-sound knowledge.” Predicting reading and spelling difficulties (Snowling & Backhouse 1996)

"The best predictor of reading difficulty in kindergarten or first grade is the inability to segment words and syllables into constituent sound units (phonemic awareness)" Lyon, G. R. (1995). Toward a definition of dyslexia. Annals of Dyslexia, 45, 3-27.

“The ability to hear and manipulate phonemes plays a causal role in the acquisition of beginning reading skills”. Smith, Simmons, & Kame'enui, 1998

The effects of training phonological awareness and learning to read are mutually supportive. "Reading and phonemic awareness are mutually reinforcing: Phonemic awareness is necessary for reading, and reading, in turn, improves phonemic awareness still further." Shaywitz. S. (2003). Overcoming dyslexia: A new and complete science-based program for reading problems at any level. New York: Knopf.

Adams, M. J., Foorman, B. R., Lundberg, I., & Beeler, T. (1998). The elusive phoneme: Why phonemic awareness is so important and how to help children develop it. American Educator, 22(1-2), 18-29.

Anderson, R. C. (1992). Research foundations for wide reading. Paper commissioned by the World Bank. Urbana, IL: Center for the Study of Reading.

Anderson, R. C., & Pearson, P. D. (1984). A schema-theoretic view of basic processes in reading. In P.D. Pearson, R. Barr, M. L. Kamil, & P. Mosenthal (Eds.), Handbook of Reading Research (pp. 255-291). New York: Longman.

Blachman, B. A., Ball, E. W., Black, R. & Tangel, D. M. (2000). Road to the Code. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

Felton, R. H., & Pepper, P. P. (1995). Early identification and intervention of phonological deficits in kindergarten and early elementary children at risk for reading disability. School Psychology Review, 24, 405-414.

Felton, Rebecca H., Wood, Frank B. (1992). A Reading Level Match Study of Nonword Reading Skills in Poor Readers with Varying IQ. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 25, 5, 318-326.

Foorman, B. R., Francis, D. J., Shaywitz, S. E., Shaywitz, B. A., & Fletcher, J. M. (1997). The case for early reading intervention. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Foorman, Barbara R., And Others. (1996). Relation of Phonological and Orthographic Processing to Early Reading: Comparing Two Approaches to Regression-Based Reading-Level-Match Designs. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88, 4, 639-652.

Torgesen, J. K., & Bryant, B. T. (1994). Phonological awareness training for reading. Austin, TX: Pro-ed.

Chunks – onset + rime awareness

Word Building – onset + rime awareness

Initial Sounds – onset + rime awareness, phoneme transposition

Spelling – phonemic awareness, phonic knowledge, visual memory, sequencing

Spelling Quiz - phonemic awareness, phonic knowledge, visual memory, sequencing

Jigsaw (game) – phonemic awareness, auditory discrimination and phonic knowledge

Vowel Ladder (game) – phonemic awareness, auditory discrimination, phonic knowledge, blending, decoding/encoding skills

Alphabet (Supplementary Activities) – phonic knowledge, phonemic awareness

Spelling – auditory discrimination, phonemic awareness, decoding/encoding skills

Syllables – auditory syllabification

Short Vowels (Supplementary Activities/Phonological) – auditory discrimination and decoding/encoding

Initial Sounds (Supplementary Activities/Phonological) – Phonemic awareness, auditory discrimination, phonic knowledge

Sound Splits - understanding phoneme-grapheme correspondence

Word Ladder – phoneme transposition

Sound Chunks– blending onset and rime

Find the Letters – phoneme/grapheme matching

Drop – sequencing letters in a word

Word Building – sequencing letters in a word

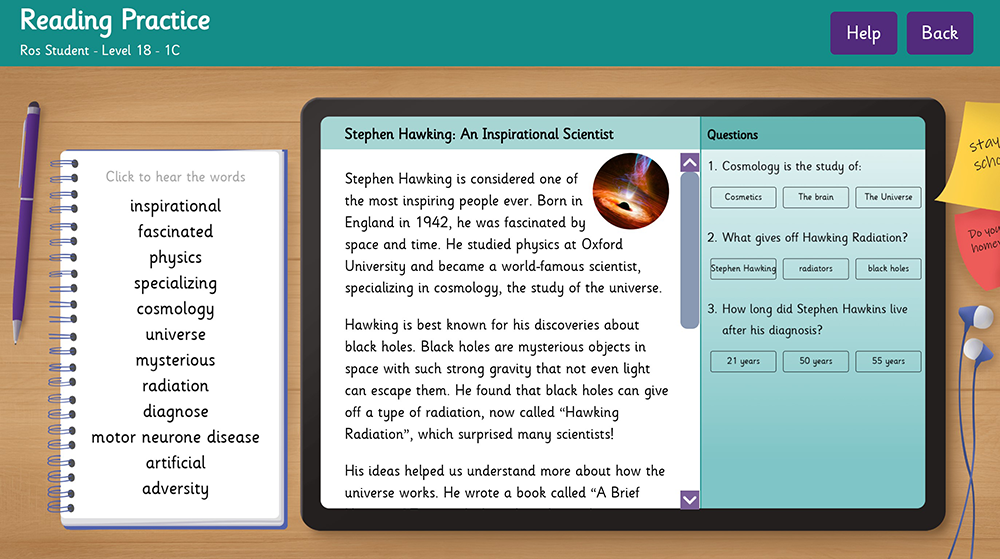

Reading Practice– reading passages and answering questions

StepsWeb now includes a Phonics Check which offers a fast, reliable way to assess your students' phonic knowledge without the time-consuming admin. The StepsWeb Phonics Check uses the same principles as traditional checks, but it is completed and marked online, meaning a whole class can be tested online together, rather than tested and marked individually.

Unlike the paper-based phonics checks, the StepsWeb Phonics Check is in two parts - one focusing on encoding, and the other on decoding. This allows educators and parents to identify and address specific difficulties. Once your students have completed both parts of the Phonics Check, you can go to your Educator account to see a comprehensive overview of their results.

Anderson, R. C. (1992). Research foundations for wide reading. Paper commissioned by the World Bank. Urbana, IL: Center for the Study of Reading.

Anderson, R. C., & Pearson, P. D. (1984). A schema-theoretic view of basic processes in reading. In P.D. Pearson, R. Barr, M. L. Kamil, & P. Mosenthal (Eds.), Handbook of Reading Research (pp. 255-291). New York: Longman.

American Federation of Teachers (1999). Building on the best, learning from what works: seven promising reading and English language arts programs. Washington DC. In http://www.aft.org/edissues/whatworks/index.htm.

Blachman, B. A., Ball, E. W., Black, R. & Tangel, D. M. (2000). Road to the Code. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

Carnine, D. W., Silbert, J., & Kameenui, E. J. (1997). Direct instruction reading (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill/Prentice-Hall.

Juel, C. (1991). Beginning reading. In R. Barr, M. L. Kamil, P. B. Mosenthal, & P. D. Pearson (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (pp. 759-788). New York: Longman.

Juel, C. (1988). Learning to read and write: A longitudinal study of 54 children from first through fourth grades. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80, 437-447.

Kame'enui, E. J. & Simmons, D. C. (1990). Designing instructional strategies: The prevention of academic learning problems. Columbus, OH: Merrill Publishing Company.

Kame'enui, E. J., & Simmons, D. C. (2000). Planning and evaluation tool for effective schoolwide reading programs. Eugene, OR: Institute for the Development of Educational Achievement.

Kame'enui, E. J., Carnine, D. W., Dixon, R. C., Simmons, D. C., & Coyne, M. D. (2002). Effective teaching strategies that accommodate diverse learners (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Kame'enui, E. J., Simmons, D. C., Baker, S., Chard, D. J., Dickson, S. V., Gunn, B., Smith, S. B., Sprick, M., & Lin, S. J. (1997). Effective strategies for teaching beginning reading. In E. J. Kame'enui, & D. W. Carnine (Eds.), Effective Teaching Strategies That Accommodate Diverse Learners. Columbus, OH: Merrill.

Kaminski, R. A., & Good, R. H., III (1998). Assessing early literacy skills in a problem-solving model: Dynamic indicators of basic early literacy skills. In M. R. Shinn (Eds.), Advanced applications of curriculum-based measurement. New York: Guildford.

Kaminski, R. A., & Good, R. H., III (1996). Toward a technology for assessing basic early literacy skills. School Psychology Review, 25(2), 215-227.

Liberman, I. Y., & Liberman, A. M. (1990). Whole language vs. code emphasis: Underlying assumptions and their implications for reading instruction. Annals of Dyslexia, 40, 51-76.

Nagy, W., & Anderson, R. C. (1984). How many words are there in printed school English? Reading Research Quarterly, 19, 304-330.

Rayner, K. & Pollatsek, A. (1989). The psychology of reading. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Reading fluency is the ability to read connected text rapidly, effortlessly and automatically (Hook & Jones, 2004; Meyer, 2002; National Reading Panel, 2000). Readers must develop fluency to make the bridge from word recognition to reading comprehension (Jenkins, Fuchs, Vandern Broek, Espin & Deno, 2003).

“Many poor readers have difficulty reading fluently because they do not possess an adequate sight vocabulary and must labour to decode many of the words in the reading passages. [...] Fluent reading requires that most of the words in a selection be sight words. When a selection contains too many difficult (nonsight) words, the reading material will be too arduous and frustrating for the reader" (Burns, Roe & Smith, 2002; Jenkins et al., 2003).

Research by Sally Shaywitz using fMRI scanning has identified that there are three key areas of the brain for reading. These are all in the left hemisphere. Broca’s area and the parietal-temporal area are involved in decoding (word analysis) and the Visual Word Form Area (occipito-temporal area) is involved in recognising the word holistically from its visual and orthographic pattern.

This process is known as orthographic mapping. To utilise orthographic mapping and therefore read fluently, the occipito-temporal area must be functional.

When a word is first met, Broca’s area and the parieto-temporal area are employed to decode it. This may happen several times. However, after several repetitions, a neural model of that word is created, which is then stored in the occipito-temporal area. Once this has happened, the word can now be accessed automatically using orthographic mapping and reading fluency has been achieved.

Sally Shaywitz’s research has also identified that dyslexic learners have an impaired occipito-temporal and are unable to develop the same fluency and automaticity. As a compensatory measure, Broca’s area overdevelops – in other words, the wrong strategies are being employed.

From the very beginnings of literacy, teachers need to incorporate enough activities to activate the occipito-temporal area. They also need to ensure that each learner has enough repetitions of each word to create and automatically retrieve the neural model of that word using orthographic mapping.

It is important to be aware that, although the Visual Word Form Area is a visual recognition area of the brain, instant visual recognition also depends on an understanding of the phonological and orthographic structures of the word. Phonic knowledge and phonological awareness are therefore also important factors in this process.

All the word activities in StepsWeb develop fluency, since it is through repetition of words that automaticity develops. However, there are a number of activities which specifically target this aspect.

Find the Word – sight vocabulary, visual recognition

Choose the Word – sight vocabulary, using/choosing words in context

Word Flash – instant word recognition. Note: This activity (together with the speed reading activities in the workbook courses) is specifically designed to activate the occipito-temporal area and promote effective orthographic mapping strategies.

Visual Memory – word recognition, visual and spatial memory

StepsWeb includes the Visual Recognition Test which measures how many milliseconds it takes a user to visually recognise a known word. Supporting research in this field indicates that, if a person can visually recognise a word in 150 ms or faster, they are utilising the Visual Word Form Area (occipito-temporal) of the brain. In other words, they are using orthographic mapping, rather than consciously decoding the word.

The StepsWeb Visual Recognition Test was evaluated by Auckland University researchers who identified elements needing adjustment during its development to ensure full research validity. The researchers produced an academic report which you can download from our Support Site article: Visual Recognition Test Research.

The report identified that children’s recognition speed increases from age 5 to 9, and that slower than average recognition speeds were an indicator of potential literacy difficulties. There was a statistically valid correlation between visual recognition speed and teacher evaluation of literacy levels. The report also identified that visual recognition speed scores were a valid predictor of later literacy difficulties even with five-year-olds. (Cowie & Plimmer, 2017)

This test and the ongoing measurement of visual recognition speed are therefore an indicator of whether a learner is utilising the Visual Word Form Area, or is over-dependent on the decoding areas of the brain. Educators can set this test for their students on StepsWeb, which enables them to see whether a student is below the expected speed for their age. It also enables them to track progress as their students develop orthographic mapping.

“Exploring the relation between visual recognition speed, teacher literacy assessment and age. Analysis of the StepsWeb Visual Recognition Speed Test.” (Cowie & Plimmer, 2017)

“To gain meaning from text, students must read fluently.” (Kuhn & Stahl, 2000)

Fluency refers to the ability to read words automatically, with no noticeable cognitive or mental effort. In other words, it implies that the learner has developed word recognition skills which enable the word to be recognised as a whole unit, rather than having to be decoded. (Juel, 1991, see references)

Fluency is essential if vocabulary and comprehension are to develop. If a learner has to concentrate on the decoding process, he/she cannot simultaneously follow the sense of the passage effectively. Fluency depends on an area of the left hemisphere of the brain, known as the ‘occipito-temporal’, which research shows is inactive in many dyslexic learners. (Shaywitz. S. (2003). Overcoming dyslexia: A new and complete science-based program for reading problems at any level. New York: Knopf.)

“Proficient readers are so automatic with each component skill (phonological awareness, decoding, vocabulary) that they focus their attention on constructing meaning from the print.” (Kuhn & Stahl, 2000)

Cowie, S., & Plimmer, B. (2017). Exploring the relation between visual recognition speed, teacher literacy assessment and age: Analysis of the StepsWeb Visual Recognition Speed Test for ages 5.0–8.9. Auckland, New Zealand: University of Auckland. Report prepared for Learning Staircase Ltd.

Juel, C. (1991). Beginning reading. In R. Barr, M. L. Kamil, P. B. Mosenthal, & P. D. Pearson (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (pp. 759-788). New York: Longman.

Stahl, S. A., & Shiel, T. R. (1999). Teaching meaning vocabulary: productive approaches for poor readers. In Read all about it! readings to inform the profession (pp. 291-321). Sacramento, CA: California State Board of Education.

Stanovich, K. E. (1986). Matthew effects in reading: Some consequences of individual differences in the acquisition of literacy. Reading Research Quarterly, 21, 360-406.

An understanding of vocabulary is crucial if the learner is to gain meaning from text. There is a difference between oral vocabulary and reading vocabulary. Oral vocabulary refers to the words which the child uses in speaking and listening. Reading vocabulary refers to the words the learner recognises in print. Children enter school with a large oral vocabulary, estimated to be about 6,000 words. The average high school pupil knows about 45,000 words by Years 11 (Stahl, 2004).

Vocabulary can be developed through both direct and indirect instruction. Indirect instruction includes the student’s own reading and oral language practice/interaction. Direct instruction involves teaching words using a range of word-learning strategies.

“Most words require 20 exposures in context before an adequate grasp of their meanings is acquired.” (McKenna, 2004)

The National Reading Panel (2000) concluded that computer programs are helpful in teaching vocabulary. It also noted that the process of teaching vocabulary before reading the text is helpful.

Note: this can be achieved by creating pre-reading, customised vocabulary lists in StepsWeb before tackling the printed passage.

The range of activities in StepsWeb ensures that every word which is taught as a reading/spelling word is also seen and used in context, often in a variety of ways. The following activities specifically develop vocabulary:

Choose the Word – sight vocabulary, using/choosing words in context

Sentence Builder – sight vocabulary, sequencing, using words in context, syntactic awareness

Word Search – sight vocabulary, visual recognition, visual discrimination, visual sequencing, using words in context (when doing printed cloze activity)

Homophones (Wordlists) – 40 lists of homophones

Everyday Topics (Wordlists) – 1,000+ words divided into topic lists (all activities provided for every list)

Personal/Custom Lists – ability to enter lists of words relevant to individual learners or classes, enabling teachers/parents to pre-teach vocabulary and reading words. Learners can see and use the words in a variety of contexts, utilising all the above activities.

Stargame – printable set of materials which can be used for games requiring the learner to generate their own sentence for each word.

Four in a Row (game) – homophones option

Word study lists (Wordlists) - including prefixes, suffixes and word roots

Jigsaw (game) – verbal reasoning activities involving processing meaning and seeing links.

Definitions – matching words to their definitions

Clues – reading and understanding less formal language to solve a clue.

Label the Picture

Reading Practice – reading passages and answering questions

Morphology (Built into Course and also available as separate lists) Note: This replaces word study lists

Advanced vocabulary is introduced from Level 5 of the Course, with words being continually revised until completely mastered. These lists are also available through the Wordlists section.

“Learning, as a language-based activity, is fundamentally and profoundly dependent on vocabulary knowledge. Learners must have access to the meanings of words that teachers, or their surrogates (e.g., other adults, books, films, etc.), use to guide them into contemplating known concepts in novel ways (i.e. to learn something new).” (Baker, Simmons, & Kame'enui, 1998) See References

“The importance of vocabulary knowledge to school success, in general, and reading comprehension, in particular, is widely documented.” (Becker, 1977; Anderson & Nagy, 1991; see References)

“Children who enter with limited vocabulary knowledge grow much more discrepant over time from their peers who have rich vocabulary knowledge.” (Baker, Simmons, & Kame'enui, 1997; see References).

Ogle, D. (1986). K-W-L: A teaching model that develops active reading of expository text. The Reading Teacher, 39, 564-570.

Rayner, K. & Pollatsek, A. (1989). The psychology of reading. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Simmons, D. C., & Kame'enui, E. J. (1990). The effect of task alternatives on vocabulary knowledge: A comparison of students with and without learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 23, 291-297, 316.

Simmons, D. & Kame'enui, E. (1999) Optimize. Eugene, OR: College of Education, Institute for Development of Educational Achievement, University of Oregon.

One core principle of StepsWeb is that all words are seen and used in context. A word may be initially introduced in a word family, or example of a phonic pattern. It will then be used and seen in a variety of different contexts.

This not only develops a full understanding of its meaning and usage; it also provides the extensive reinforcement needed by some learners to develop true automaticity.

Reading Practice – reading passages and answering questions

Choose the Word – sight vocabulary, using/choosing words in context

Sentence Builder – sight vocabulary, sequencing, using words in context, syntactic awareness

Word Search – sight vocabulary, visual recognition, visual discrimination, visual sequencing, using words in context (when doing printed cloze activity)

Definitions – matching a word with its more formal, dictionary-style definition.

Clues – reading and understanding less formal language to solve a clue.

Homophones (Wordlists) – Word usage, comprehension

Everyday Topics (Wordlists) – Thousands of words divided into topic lists

Personal/Custom Lists – ability to enter lists of words relevant to individual learners or classes, enabling teachers/parents to pre-teach vocabulary and reading words. Learners can see and use the words in a variety of contexts, utilising all of the above activities.

Stargame – printable set of materials which can be used for games requiring the learner to generate their own sentence for each word.

Four in a Row (Game) – homophones/word study options

Grammar activities – building awareness of word forms (verb, adjective, noun) and verb forms and tenses

Word study (Wordlists) - including prefixes, suffixes, phonic and orthographic patterns and word roots.

Comprehension is described as the ‘active and intentional thinking, in which the meaning is constructed through interactions between the text and the reader (Durkin, 1973, see References). It is described as a complex cognitive process, which depends on all of the other four Big Ideas in addition to the prior knowledge and engagement of the reader.

The key causes of reading comprehension difficulties (Kame'enui & Simmons, 1990) are:

Ogle, D. (1986). K-W-L: A teaching model that develops active reading of expository text. The Reading Teacher, 39, 564-570.

Rayner, K. & Pollatsek, A. (1989). The psychology of reading. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Robbins, C., & Ehri, L. C. (1994). Reading storybooks to kindergartners helps them learn new vocabulary words. Journal of Educational Psychology, 86(1), 54-64.

Felton, Rebecca H., Wood, Frank B. (1992). A Reading Level Match Study of Nonword Reading Skills in Poor Readers with Varying IQ. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 25, 5, 318-326.